Are There Any Moving Images That Aren’t Screendance? Hybrid Undecidability or, You Can’t Pin a Good Chimera Down…

by Marisa C.Hayes

When celebrated author Damon Knight was pressed to provide a definition of science fiction, the writer retorted, ‘Science fiction is what we point to when we say it.’1 Defining screendance may feel like an equally thorny affair. Is the artist’s intention enough to accept that a work is indeed screendance if that’s what they say it is? And what about moving images that were not initially conceived as screendance but may be understood as such by audiences? For twenty years, I’ve been listening to various curators, researchers, and audiences grapple with these questions, as they debate what screendance is or isn’t. How do we define screendance? Is it an approach? A genre of fimmaking? A genre of dance? An artistic movement? A field of research? A way of “reading” moving images? Can screendance be all of those things at once? Or perhaps none of them at all? I’ve heard all of the above proposed (and rejected) in diverse contexts that oscillate between thoughtful exchanges and dubious proclamations.

Is defining screendance even useful? I used to find it frustrating that so much time was dedicated to discussing definitions of screendance, particularly at festivals, where organizers tend to proffer their own spin on the term (full confession: I’ve done it myself!). This took us back to square one each time and detracted, I felt, from exploring the moving images themselves and the artists who make them. Yet, as a chimera par excellence, the hybrid nature of screendance invites reflection on a number of pertinent and evolving questions when approached constructively, including: What is a screen? What is dance? Is dance a uniquely human activity? (outdated dance theory texts still claim it is, while animal behaviorists have proven otherwise in recent years, which inspires yet another question: Does screendance have an anthropocentric problem?). And, as Claudia Kappenberg asks in a key article penned in 2009, “Does Screendance Need to Look Like Dance?”.2

Over time, I’ve grown to appreciate the ways in which debates about screendance resurface in new settings, languages, and cultural contexts; each with something to contribute, each reshaping a small piece of the hybrid beast we can’t quite pin down (and some of us like it this way). Instead of envisioning these debates as a perpetual return, perhaps attempting to define screendance is a case of Gertrude Stein’s “a rose is a rose is a rose”, a mantra of perpetual motion that is never quite repeated the same way and carries us to a new place of understanding. Indeed, fifteen years ago, The International Journal of Screendance launched its inaugural issue entitled, “Screendance Has Not Yet Been Invented”3, a provocation that reimagines film theorist André Bazin’s 1946 statement that “cinema has not yet been invented”. His writing served as an important catalyst for considering the ontology of moving images and their potential, another ongoing discussion that asks us to consider not just what moving images are, but what they can be.

While I’ve observed some of my own screendance students struggle with this undecidability, I’ve witnessed many more who thrive in response to its possibilities. Screendance is constantly shifting in response to the cultural and technological currents of its time, as do all artistic movements, modes of production, and transmission. But instead of defining boundaries, what if we blurred them? What if we, as artists, scholars, curators and audiences, committed to embracing open definitions that provide ample space in which multiple approaches and diverse practices exist simultaneously? As Donna Haraway envisioned, “the future is plural”. Perhaps a good definition inspires a constellation of questions rather than answers.

At this point, dear readers, you may be thinking, “That’s all fine and well, but not once have you offered an explanation of what screendance can be, singular or plural”. I assure you that my intention is not a facetious one, and in the open vein of this short text, I’d like to offer one deceptively simple clue. It can be found in revisiting the device that gave us the modern moving image4. The cinematograph, like screendance, is a hybrid term that led to its more familiar shortened form, cinema. The word’s etymology combines the ancient Greek for writing (recording) and movement. Moving images, as we know them today, trace their source to this device. But then who decides what recorded movements constitute a dance?

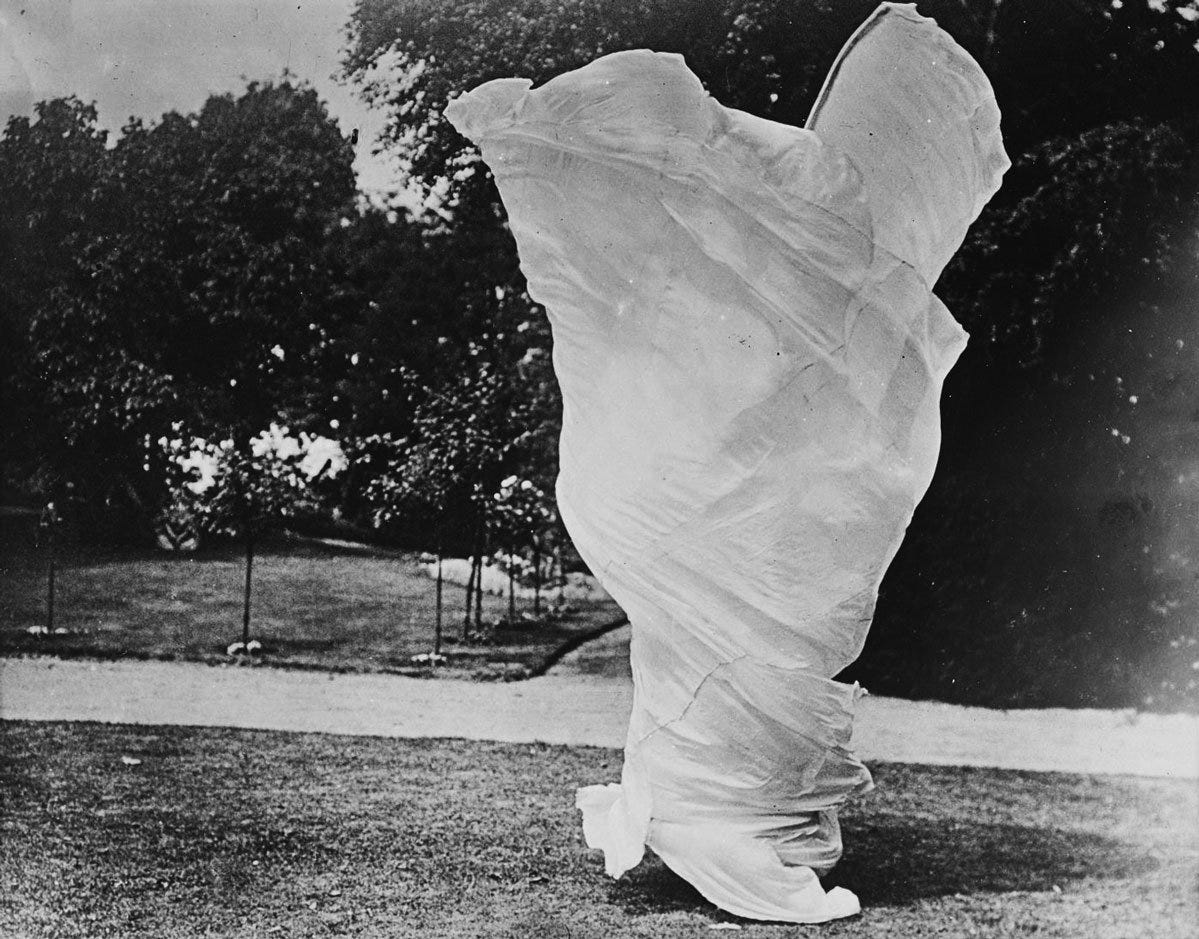

Curiously, I find opinions much more divided on the question of defining dance than that of the screen. With that in mind, it’s useful to recall that in the west, dance once struggled to assert itself as an independent art form from opera, while centuries later, some critics claimed Loie Fuller’s modern choreography was not dance at all. A few decades later, history repeated itself when many postmodern choreographers received the same treatment. And on it goes. As reductive as these examples are, they demonstrate that across centuries, dance has reinvented itself and expanded exponentially. Rather than being any one thing, dance has become plural and continues to usher in new ways of moving and being present in the world, which often face initial resistance. And once you begin looking at movement on screen, screendance appears to be everywhere: in the way a character walks during a fictional feature film, in the swirling composition of letters within a commercial advertisement, in the swinging handheld camera of an experimental film, or in the editing rhythms of found footage, just to name a few. Who is to say that today’s movement is not the root of tomorrow’s dance? Perhaps screendance really is what we point to when we say it.

Endnotes:

A definition the author first described in a review column for Lester del Rey’s Science Fiction Adventures in November 1952 and was later collected in In Search of Wonder (1956). It is still widely quoted as a definition of science fiction. The documentary described above is an episode entitled ‘Damon Knight’ from James Gunn’s The Literature of Science Fiction Film Series, 1960-1970.

Claudia Kappenberg, “Does Screendance Need to Look like Dance?” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media, 5(2–3), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1386/padm.5.2-3.89/1

Cinephiles will no doubt take issue with this statement, as cinema’s history is built upon a number of pre-cinematic and photographic devices, the oldest of which is likely shadow puppet theatre. Various cultures have developed projected images and lights in multiple forms for centuries, but my reference to the cinematograph here is intended to evoke the possibility of both moving and recorded images in a format familiar to present-day viewers and which paved the way for a variety of film and video technologies.

(This is the original text.)

Biografia:

Marisa C. Hayes is an interdisciplinary writer, curator and artist, as well as a devotee of undecidability and Umberto Eco’s “The Open Work”. Currently Provost & Vice President of Academic Affairs at the Paris College of Art, she also co-edits The International Journal of Screendance. This year, she created an educational project at the intersections of the performing and visual arts for the French Ministry of Culture’s CURA program. In 2009, she co-founded the Festival International de Vidéo Danse de Bourgogne, a platform she continues to co-curate annually. Marisa contributes to a variety of print and electronic media dedicated to moving images and the performing arts.

https://videodansebourgogne.com/

Traduzione in italiano a cura del team editoriale:

Esistono immagini in movimento che non siano screendance?

Indecidibilità Ibrida, o una buona chimera non si lascia incastrare....

di Marisa C.Hayes

Quando il celebre autore Damon Knight fu spinto a fornire una definizione di fantascienza, lo scrittore rispose: “E’ fantascienza tutto ciò che riconosciamo come tale”.1 Definire la screendance potrebbe sembrare altrettanto complicato. È sufficiente l’intenzione dell’artista per accettare che un’opera sia effettivamente screendance, se è così che l'autore la definisce? E che dire delle immagini in movimento che non sono state inizialmente concepite come screendance, ma che possono essere interpretate come tali dal pubblico? Da vent’anni ascolto curatori, ricercatori e pubblico dibattere su queste questioni, mentre discutono su cosa sia o non sia screendance. Come definiamo la screendance? È un approccio? Un genere di cinema? Un genere di danza? Un movimento artistico? Un campo di ricerca? Un modo di ‘leggere’ le immagini in movimento? La screendance può essere tutte queste cose contemporaneamente? O forse nessuna di esse? Ho sentito tutte queste ipotesi venire proposte (e anche respinte) in contesti diversi, tra profondi scambi di idee e dichiarazioni discutibili.

È davvero utile definire la screendance? In passato trovavo frustrante che si dedicasse tanto tempo alla discussione sulle definizioni della screendance, specialmente nei festival, dove gli organizzatori tendono a dare la propria interpretazione del termine (confesso: l’ho fatto anch’io!). Ogni volta si tornava al punto di partenza, distraendosi, a mio avviso, dall’esplorazione delle immagini in movimento e degli artisti che le creano. Tuttavia, in quanto chimera par excellence, la natura ibrida della screendance invita a riflettere su una serie di questioni pertinenti e in continua evoluzione, se affrontate in modo costruttivo, tra cui: Che cos’è uno schermo? Che cos’è la danza? La danza è un’attività esclusivamente umana? (Testi di teoria di danza ormai superati continuano a sostenerlo, mentre gli etologi hanno recentemente dimostrato il contrario, sollevando un’ulteriore domanda: la screendance ha un problema di antropocentrismo?). E, come si chiede Claudia Kappenberg in un articolo fondamentale del 2009: “La screendance deve necessariamente assomigliare alla danza?”2

Col tempo ho imparato ad apprezzare il modo in cui i dibattiti sulla screendance riaffiorano in nuovi contesti, lingue e culture; ciascuno con qualcosa da offrire, ciascuno ridefinendo un piccolo pezzo di quella creatura ibrida che non riusciamo a fissare una volta per tutte (e ad alcuni di noi piace proprio per questo). Forse più che un eterno ritorno, tentare di definire la screendance è un po’ come il “una rosa è una rosa è una rosa” di Gertrude Stein, un mantra in perpetuo movimento che non si ripete mai esattamente nello stesso modo e che ci porta ogni volta a una nuova comprensione. In effetti, quindici anni fa, The International Journal of Screendance lanciò il suo numero inaugurale intitolato La Screendance non è ancora stata inventata,3 una provocazione che rielabora la dichiarazione del teorico del cinema André Bazin del 1946 secondo cui “il cinema non è ancora stato inventato”. Il suo scritto ha rappresentato un’importante spinta per riflettere sull’ontologia delle immagini in movimento e sul loro potenziale, un altro dibattito continuo che ci invita a considerare non solo cosa siano le immagini in movimento, ma anche cosa possono diventare.

Anche se ho osservato alcuni dei miei studenti di screendance lottare con questa indecidibilità, ne ho visti molti altri trovare ispirazione in queste diverse possibilità. La screendance continua a mutare in risposta alle correnti culturali e tecnologiche del suo tempo, come tutte le forme artistiche, i modi di produzione e trasmissione. Ma invece di definire i confini, cosa succederebbe se li sfumassimo? E se, come artisti, studiosi, curatori e spettatori, scegliessimo di accogliere definizioni aperte che offrano spazio sufficiente affinché approcci molteplici e pratiche diverse possano coesistere? Come immaginava Donna Haraway, “il futuro è plurale”. Forse una buona definizione non fornisce risposte, ma piuttosto genera una costellazione di domande.

A questo punto, cari lettori, potreste pensare: “Va bene, tutto interessante, ma finora non ci hai ancora davvero spiegato cosa possa essere la screendance, al singolare o al plurale.” Vi assicuro che la mia intenzione non è ironica e, in linea con lo spirito aperto di questo breve testo, vi voglio offrire un indizio tanto semplice quanto rivelatore. Lo si può trovare tornando al dispositivo che ci ha dato l’immagine in movimento moderna.4 Il cinematografo, come la screendance, è un termine ibrido dal quale deriva la forma accorciata e più familiare, cinema. L’etimologia della parola combina il greco antico per scrittura (registrazione) e movimento. Le immagini in movimento, come le conosciamo oggi, hanno origine in questo dispositivo. Ma allora, chi decide quali movimenti registrati costituiscono una danza?

Curiosamente, trovo che le opinioni siano molto più divise sulla definizione di danza che su quella di schermo. Tenendo presente questo, è utile ricordare che, in Occidente, la danza ha dovuto lottare per affermarsi come forma d’arte indipendente dall’opera, mentre secoli dopo alcuni critici affermavano che la coreografia moderna di Loïe Fuller non fosse affatto danza. Qualche decennio dopo, la storia si è ripetuta con molti coreografi postmoderni, che hanno ricevuto lo stesso trattamento. E così via. Per quanto riduttivi, questi esempi dimostrano che, nel corso dei secoli, la danza si è reinventata ed espansa esponenzialmente. Più che essere una cosa sola, la danza è diventata plurale e continua a introdurre nuovi modi di muoversi ed essere nel mondo, affrontando spesso resistenze iniziali. E una volta che inizi a osservare il movimento sullo schermo, la screendance sembra essere ovunque: nel modo in cui un personaggio cammina in un film di finzione, nella composizione vorticosa delle lettere in una pubblicità, nell’oscillazione della macchina da presa in un film sperimentale, o nei ritmi di montaggio del found footage, solo per citarne alcuni. Chi può dire che il movimento di oggi non sia la radice della danza di domani? Forse la screendance è davvero tutto ciò che riconosciamo come tale.

Note:

1 Una definizione che l’autore descrisse per la prima volta in una rubrica di recensioni per Science Fiction Adventures di Lester del Rey nel novembre 1952 e che fu successivamente raccolta in In Search of Wonder (1956). Ancora oggi è ampiamente citata come definizione di fantascienza. Il documentario descritto sopra è un episodio intitolato ‘Damon Knight’ da The Literature of Science Fiction Film Series di James Gunn, 1960-1970.

2 Claudia Kappenberg, “Does Screendance Need to Look like Dance?” International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media, 5(2–3), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1386/padm.5.2-3.89/1

3 Vedi: https://screendancejournal.org/index.php/screendance/issue/view/198

4 I cinefili senza dubbio contesteranno questa affermazione, poiché la storia del cinema si basa su una serie di dispositivi pre-cinematografici e fotografici, il più antico dei quali è probabilmente il teatro delle ombre. Diverse culture hanno sviluppato immagini proiettate e giochi di luce in molteplici forme per secoli, ma il mio riferimento al cinematografo qui è inteso a evocare la possibilità sia di immagini in movimento che registrate, in un formato familiare agli spettatori odierni e che ha aperto la strada a una varietà di tecnologie cinematografiche e video.

Biografia:

Marisa C. Hayes è una scrittrice interdisciplinare, curatrice e artista, nonché una devota dell'indecidibilità e del “Lavoro Aperto” di Umberto Eco. Attualmente è Provost e Vice Presidente per gli Affari Accademici al Paris College of Art e co-edita l'International Journal of Screendance. Quest’anno ha creato un progetto educativo all'incrocio delle arti performative e visive per il programma CURA del Ministero della Cultura francese. Nel 2009, ha co-fondato il Festival International de Vidéo Danse de Bourgogne, una piattaforma che continua a co-curare annualmente. Marisa contribuisce a una varietà di media stampati ed elettronici dedicati alle immagini in movimento e alle arti performative.